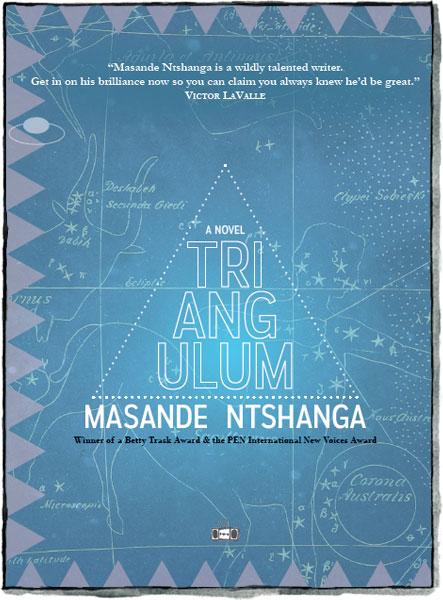

TRIANGULUM BY MASANDE NTSHANGA

Come for the unexpected convergence of Afro-futurism, eco-terrorism, alien abductions, and more. Stay for the unsettling meditations on South Africa’s dystopian past and present, the grandiose yet subversive re-imagining of humanity’s relationship to nature, and the poignant impulse, from which no character is spared, to make aliens of each other and of themselves.

Come for the classic spy thriller-cum-bildungsroman: a teen trio explores their sexuality while following breadcrumbs in pursuit of missing children (inexplicably free, of course, from adult supervision). Stay for the narrator’s hapless quest to understand her vanished mother—carrier of mental illness as well as mathematical genius—even as she herself begins to vanish, too, into a set of Russian-doll personas.

Come for the pleasure of any good puzzle. Stay because after delving so deeply into so many narratives and narrative frames, each with different sets of rules and competing conceptions of truth, you’ll want to keep questioning what’s real within the novel instead of just questioning what’s real.

Come for the high-stakes proxy wars between competing corporations and terrorist cells and megalomaniacal visionaries. Stay for the quiet assurance that novelists and readers have a quantifiable bearing on the future, too.

Come for Triangulum. Stay for next masterpiece that Ntshanga’s sure to turn out, and the next, and the next after that one. Once you open this novel, there’s no walking away.

—Review by Mekiya Walters