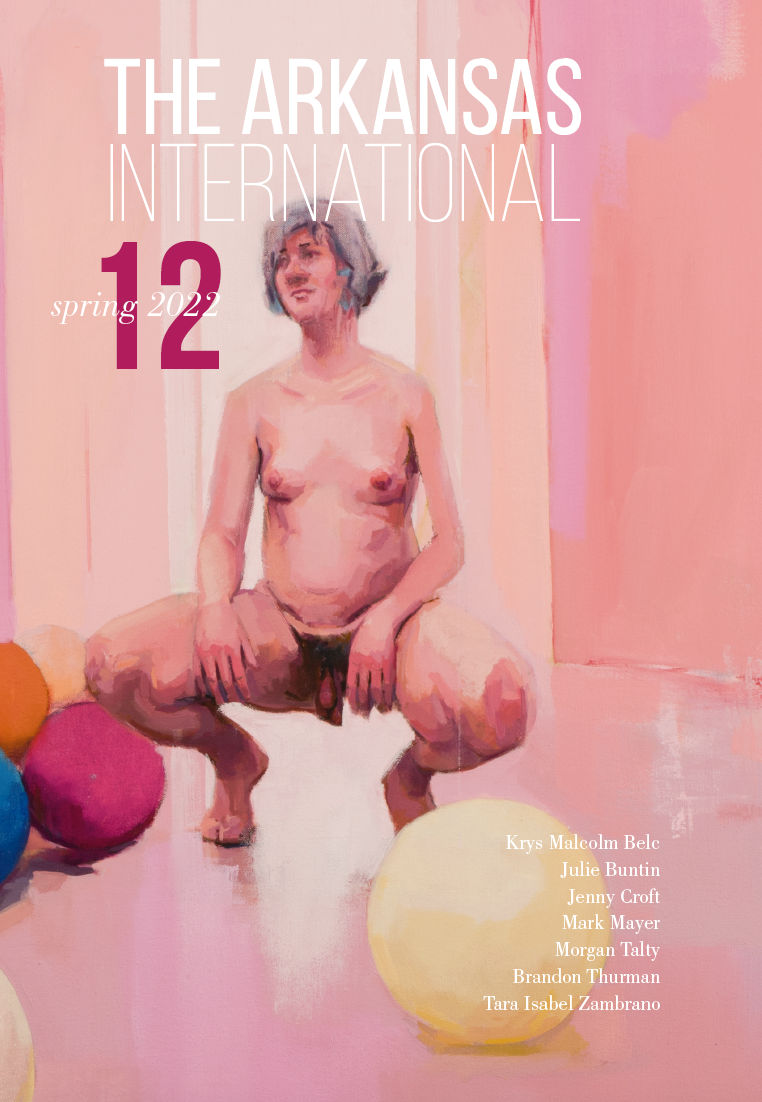

Anastasia Nikolis

The Patron Saint of Lawnmowers

When I say I wish I could just take a scissor and snip them off, people are usually horrified.

For a long time I didn’t understand why because when I imagine the process of disappearing my breasts it isn’t bloody or violent. It’s merely an acknowledgment that there has to be a process for detaching and a set of tools appropriate for that task. Like snipping a thread dangling from a seam, it’s a matter of using a tool as it was intended: in this case, to separate a part from a whole.

Most recently, I have imagined a small lawnmower. About the size a lawnmower would be if a squirrel pushed it standing on its hind legs. Lying on my back in my bed, I imagine this small lawnmower puttering over my skin, chasing the hills of my chest as they crest over my ribcage. My lover looks horrified when I describe this, but I offer reassurance: there isn’t any blood in this imagined scene. I live through it the way a lawn survives a mowing, uneventfully.

The potential for horror at this scenario comes from how you decide to freight the metaphor, “I want to mow my chest like a lawn.” People have a tendency to forget that metaphors don’t result in a uniform blend of inputs. As Mark Turner and Gilles Fauconnier explain, a metaphor pulls from two discrete input spaces and mixes them unequally, with proportions that vary according to individual interpretation. In this metaphor, flesh might respond to a lawnmower as it does when it meets any other blade, with corresponding spurts of gore. Or it might respond as grass does, with clumps of dark matted clippings and a smoother surface than when you started.

With my hands on the sheets next to my torso, I imagine what little clumps of breast would look like if breasts behaved like grass. What would they feel like? According to my metaphorical logic, they should be withered and damp, like grass clippings freshly cut. In spite of this, I don’t imagine them as damp clumps. I imagine them like the bedraggled feathers that come out of a pillow, slowly floating through the air and gathering in corners of the room.

***

Saint Agatha is the patron saint of breast cancer patients, bell founders, and bakers. Her martyrdom story is similar to many of those of the virgin saints. Like Saint Lucy or Saint Agnes or Saint Cecilia, Agatha was a young woman whose faith was tested when a horde of men tried to seduce her away from god. The story itself isn’t all that interesting to me, since there are dozens of similar stories in the Catholic tradition and its morality is so antithetical to our contemporary sensibilities. But the way Agatha has been depicted in art is something I am always enthralled by.

One of my favorite churches in Rome doesn’t have any corners. Santo Stefano Rotondo has a round floor plan with a central altar. The outer wall is frescoed with dozens of grisly saint martyrdoms: the classics like Saint Catherine with her spiked wheel, but also Saint Agatha.

Saints are often identified in artwork because of the attributes of their martyrdom, which can include the tools used to torture them, the parts of their body that were tortured, or objects that signify the populations they watch over. In some paintings of Saint Agatha, like the one on the walls of Santo Stefano Rotondo, she is shown in the middle of her torture. She is lying down, tied to a rack with her legs and waist draped in fabric. Her breasts are bare to leering men twisting her nipples with long metal pincers. Her torso has trickles of blood running over its curves. In other contexts, with consent, this could all be very erotic.

The more common depictions of Saint Agatha, which I am more fascinated by, are the ones where there is no gore. Where Agatha’s breasts are held apart from Agatha. One example is a 17th century painting by Francisco de Zurbarán, in which Saint Agatha wears a gown that is more robust than the body it is draped around. Her skirt is a bland grayish-purple, but her flat bodice and voluminous sleeves are boldly colored—deep emerald green and gold—and she has a bright red train that flows from her shoulders to the ground. Her face and body language are so nondescript that the dress becomes the focus of the painting, until you notice her tray of domed cakes. With little effort, you can understand how she became the patron saint of bakers, and how the Sicilian cake baked in her honor came to be. But it isn’t a tray of cakes. It’s two bell-shaped breasts. Two pale domes with a carefully painted shadow marking where they meet the silver.

***

Bells, cakes, feathers, grass. I find it helpful to think of breasts through metaphor because I feel so trapped when I think of them as defining features of my body or gendered experience. When I think of Saint Agatha with her tray of cakes, I imagine her giving the world the breasts they wanted so desperately. As she places the tray on a table she thinks, this is my chance. While everyone salivates, she slips away. Away from her breasts, away from the gaze of others, and away from the story of her martyrdom, so she can devise new ways of relating to her body.

There aren’t very many models for thinking about the relationship between the self and the body. Basically, there are two: as an objectified body or an active one. We all know how the gaze of others can objectify and define a body and a self. After all, Agatha’s story isn’t one where she internally validates her experience and registers a transformation to womanhood. It’s a story where she becomes a woman when her breasts are sexed and sexualized. From Simone de Beauvoir to Franz Fanon to Kimberlé Crenshaw, many theorists have talked about how individuals don’t think of themselves as belonging to a particular group based on their appearance until they encounter someone else imposing beliefs on their body. This phenomenon is only amplified in populations that are marginalized along intersecting axes of power.

One of the main ways to counteract a self-defined-by-others is to define the self in relation to agency. To define the body according to what the body can do. Can it run? Can it bleed? Can it birth? Can it make art? Extending from this line of thinking, so much (white) feminist art of the late 20th century revels in the visceral reality of what the body can do. But these artists also often conflate other kinds of female accomplishments with the female body’s reproductive organs.

Think of Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party, where each ceramic vulva plate is more elaborate than the last. These labia stand in for the other accomplishments of women like Emily Dickinson and Elizabeth I, women who are otherwise known for their verbs: writing and ruling.

Think of Carolee Schneemann’s work of performance art, “Interior Scroll.” In which she was filmed naked, pulling a scroll out of her vagina to “introduc[e] the possibility of an erotic woman who may be ‘primitive, devouring, insatiable, clinical, obscene; or forthright, courageous, integral.’”[1] Schneemann wants us to see a woman in verbs—being and devouring—through her genitalia.

After such a long history of objectification in white western patriarchal traditions, it was important for these artists to show how human the female body is and the power it can harness in its viscerality. The female body as a visceral, bleeding, leaking, birthing, resilient human force is staggeringly important. But I am also leery of a critic who once said something like, “women write and create about their bodies because it is the only thing they have control over in a patriarchal world.”

***

What if your body can’t do these things? Or, what if defining your body according to this metric of verbs feels antithetical to your sense of self and body? What are the alternatives?

The philosophers Rachel Alsop and Kathleen Lennon asked the same question and proposed the model of the “expressive body”: a body that is defined by both the self and others. According to their model, the expressive body is ever changing and constantly morphing based on inter-subjectivity and interdependence between its self and others.[2]

I like the direction that Alsop and Lennon are heading. I like how they assert that the two most prevalent models for understanding our selves in relation to our bodies just aren’t enough. But it all feels too esoteric for me. Personally, I’m more inclined to parsing the metaphorical connections between my body and Saint Agatha’s. Between my body and damp grass.

***

There is no universally agreed-upon medical term for a person with large breasts. Doctors will call it breast hypertrophy or macromastia or gigantomastia. Some say that breast hypertrophy is the umbrella category under which the other two terms fall.[3] Others say the three terms are entirely interchangeable. Regardless of terminological choice, the terms all share a common preoccupation with the weight of breast tissue as the most salient way to define large breasts, paying less attention to other factors like shape or density or how breast size impacts quality of life.

People who seek out breast reduction surgery, or mammoplasty, aren’t typically pursuing it because they are concerned about the specific weight of their breasts. I certainly wasn’t. They often pursue it because they are displeased with their appearance or because they are experiencing one of the many symptoms associated with macromastia, such as persistent neck and back pain, tingling in their upper extremities, spine curvature, restricted movement, blackouts, or shoulder grooves from bra straps.

Most doctors are sympathetic to their patients who catalog these kinds of symptoms. They dutifully record them and they do believe that these symptoms are enough to recommend mammoplasty. In fact, myriad studies unequivocally demonstrate that quality of life improves among patients who undergo breast reduction surgery.[4] In spite of this, clinical diagnosis of large breasts and eligibility for breast reduction surgery is most often determined by how much the resected amount of breast tissue weighs, which is a measurement that can’t be taken until after the surgery is performed.

In other words, if someone undergoes breast reduction surgery, and wants insurance to pay for it, the official diagnosis isn’t typically based on the symptoms that come from the patient’s embodied experience. Instead, patients are tentatively given a diagnosis of having large breasts based on the estimated objective (objectified?) weight of the tissue that will be removed. Then, they have to hope that a scale will register the weight required to confirm diagnosis after the surgery is completed.

Dear god, dear Agatha, just one to two kilograms, please, thank you, amen.

Over the past ten years, insurance companies are increasingly denying coverage to patients who pursue breast reduction surgery because of the discrepancy between anticipated weight and actual weight of breast tissue removed.[5]

You can almost imagine it, can’t you? Saint Agatha transformed into the patron saint of validated mammoplasty, weighing tray after tray of resected breast tissue. If it weighs enough, she consecrates your valid medical condition. If it doesn’t, you’re referred elsewhere to deal with your psychosis: metaphor theory, a dinner party with labia plates, a room without corners for feathers to gather in.

***

I started investigating breast reduction surgery more than a decade ago, when I began blacking out in a college class. After a few hours of feeling increasingly cloudy, my neck feeling increasingly tight, I stumbled to the bathroom and locked the door. I sat on the floor and unhooked my bra so I could restore circulation. I sat there breathing deeply until the grayed out dots started to recede from my field of vision. I have logged these symptoms and others in my medical records ever since. If I have enough of a history of symptoms, my doctor will feel comfortable enough to approach an insurance company to recommend me as a candidate for the procedure.

I am a candidate for the procedure. However, the longer I have dealt with them, the physical symptoms are kind of beside the point.

***

When I’ve said I wish I could just snip them off, people are usually horrified.

I think part of it is because people are (rightfully) conditioned to be leery of self-harm. But I think it is also because we don’t have a good model for understanding this kind of body relationship: one in which I do identify as a woman, but I don’t identify with my breasts. We have limits to how we define and validate our relationships to our bodies.

***

When I’ve said I wish I could just snip them off, people look uncomfortable. They cajole. They say I’m beautiful the way I am. They ask if I’ve bought a new bra recently.

They get angry. Shouldn’t I accept and love my body at any size, any weight, with all of its particular features and characteristics?

They get political. In pursuing breast reduction surgery, aren’t I contributing to the long history of self-hatred based on societal gender norms?

Am I?

***

Until the DSM was updated in 2013, when a person fixated on a particular body part and imagined shrinking it, changing it, amplifying it, or removing it, they were diagnosed with Body Dysmorphic Disorder and evaluated for psychosis. Now, they are still diagnosed with BDD but are treated similarly to people who live with OCD. Their thoughts about their bodies are no longer considered psychotic, but instead as brain misfirings, or cognitive distortions.

When treating OCD or BDD, a therapist will often help the individual identify the cognitive distortion they are making and work with them to identify it as such. For example, someone with BDD might start fixating on their prominent nose or pointy elbows. They become convinced that there is something wrong with that nose or elbow and they will pursue surgery to “fix” this body part. But studies have shown that surgery doesn’t alleviate the fixation in people living with BDD. Instead, they will shift their fixation to a new body part after surgery. These studies have led psychologists to conclude that it was never the body part that was at issue at all. It was always a cognitive distortion.

In the case of breast reduction surgery, fixation doesn’t seem to apply, since other studies show that quality of life unequivocally improves among people who pursue it. And yet, there is still the sense that someone pursuing breast reduction surgery is fixating in ways that are similar to those with eating disorders and distorted body image.

This is where those questions about dismantling gender norms and pushing against the control of women’s bodies start to crop up. This is where people question whether a person is pursuing mammoplasty as an act of self-hatred or self-validation.

Why can’t it be an act of self-care? Validating, I suppose, but also as banal as trimming your nails.

***

Dear god, dear Agatha.

When I’ve said I just want to snip them off, what I mean is that I want a better way to describe why these sacks of yellow fat[6] aren’t part of my sense of my self.

What I mean is that I just think of them as things to be dealt with.

Like weights that need to be carried from one place to the next.

Like a thread that’s come loose.

Like grass that’s too long.

Like bell-shaped cakes on a platter waiting to be served.

[1] https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/schneemann-interior-scroll-p13282

[2] Rachel Alsop and Kathleen Lennon, “Aesthetic surgery and the expressive body,” Feminist Theory, 19, no. 1 (2018): 95-112. doi: 10.1177/1464700117734736

[3] Anne Dancey*, M. Khan, J. Dawson, F. Peart, “Gigantomastia – a classification and review of the literature,” Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery: JPRAS, 61, no. 5 (2008): 493-502. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2007.10.041

[4] There are many studies you might refer to that demonstrate these findings. Here are just a few examples: Cabral IV, Garcia ED, Sobrinho RN, et al. “Increased capacity for work and productivity after breast reduction,” Aesthetic Surgery Journal. (2017); Freire M, Neto MS, Garcia EB, Quaresma MR, Ferreira LM. “Functional capacity and postural pain outcomes after reduction.” Plastic Reconstrive Surgery. (2007); Hernanz F, Fidalgo M, Munoz P, Noriega MG, Gomez-Fleitas M. “Impact of reduction mammaplasty on the quality of life of obese patients suffering from symptomatic macromastia: A descriptive cohort study.” Journal of Plastic Reconstructive Aesthetic Surgery (2016); Gonzalez MA, Glickman LT, Aladegbami B, Simpson RL. “Quality of life after breast reduction surgery: A 10-year retrospective analysis using the Breast Q questionnaire. Does breast size matter?” Ann Plast Surg. (2012); Coriddi M, Nadeau M, Taghizadeh M, Taylor A. “Analysis of satisfaction and well-being following breast reduction using a validated survey instrument: The BREAST-Q.” Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. (2013)

[5] Stefanos Boukovalas, M.D.; Boson, Alexis L. B.S.; Padilla, Pablo L. M.D.; Sljivich, Michaela M.D.; Tran, Jacquelynn P. M.D.; Spratt, Heidi Ph.D.; Phillips, Linda G. M.D., “Insurance Denials in Reduction Mammaplasty: How Can We Serve Our Patients Better?” (2020). Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000006968

[6] Rachel Bloom, “Heavy Boobs,” YouTube, March 28, 2016, video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aZx5zfkG6oU

Anastasia Nikolis is the visiting artist-in-residence at St. John Fisher College and poetry editor at the literary translation press Open Letter Books. A creative writer and a scholar, her research focuses on confession and intimacy as linguistic constructions in post-1945 American poetry. Her critical work has appeared in Adroit Journal, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. She holds a PhD in English from the University of Rochester.